Urethral Stricture

Introduction to Urethral Stricture

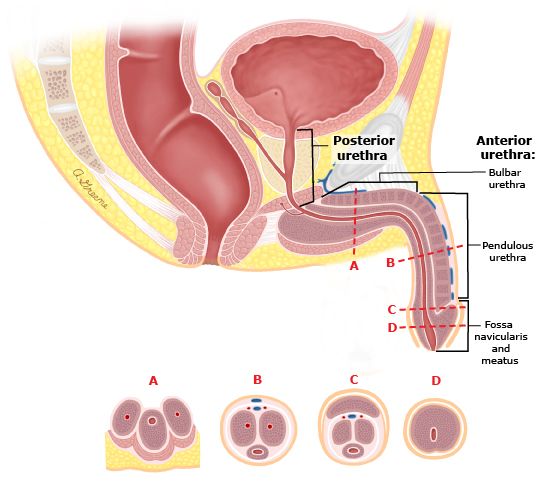

Urethral Anatomy by division of the Anterior and Posterior Urethra

The urethra's main job is to empty urine from the kidneys, which drain to the bladder. When a scar forms from swelling, injury, or infection, this scar can block the flow of urine in this tube. The formation of scar in the urethra is called a urethral stricture. This may lead to some difficulty in emptying the bladder or even the inability to urinate – called urinary retention. The development of scar tissue in the urethral is called urethral stricture disease (USD). Although this is referred to as a “disease,” it is not contagious or generally associated with other medical problems.

Anatomy

The male urethral is divided up into the anterior urethra and the posterior urethra. The posterior urethra is subdivided into the bladder neck, prostatic urethra and the prostatic urethra. The anterior urethra is then subdivided into the bulbar urethra, pendulous urethra, fossa navicularis, and meatus.

Posterior urethra

Bladder Neck – the bladder neck is the opening in the bladder base which allows urine to pass into the prostatic urethra. It is particularly important because it is responsible for prevention of urine leakage. When the bladder is not emptying, the bladder neck remains contract and thus no urinary leakage occurs.

Prostate – the prostatic urethra is simply the urethra that runs through the prostate. Within this portion of the urethra, prostate tissue may grow and cause obstructive symptoms (i.e. slow flow, difficulty emptying, start-and-stop stream, etc). This is called Benign Prostatic Enlargement (BPE) and may require treatment with medications or surgery.

Membranous Urethra – the membranous urethra is a small portion of the uretha just past the prostatic urethra. It is surrounded by your external urinary sphincter muscles. These are the same muscles used when Kegel exercises are performed and allow you to stop your urine flow mid-stream. It is critically important in maintaining continence and may be affected by surgery, radiation, or traumatic injury.

Anterior Urethra

Bulbar Urethra – the bulbar urethra is where the urethra makes its turn under the pubic bone (pubic symphysis). It is the area that has large blood supply and is surrounded by a dilated meshwork of spongy veins called the corpus spongiosum. Because of its location directly behind the scrotum, it is often the location for any straddle injuries which may lead to scar formation.

Pendulous Urethra (Penile urethra) – the penile urethra is the longest segment of urethra and it is surround by a symmetric meshwork of spongy veins – the corpus spongiosum. Often in the case of a urethral stricture, there will also be some scar formation in the corpus spongiosum, called spongiofibrosis.

Fossa Navicularis – the fossa navicularis is the portion of the male urethra which is in the glans or head of the penis.

Urethral meatus – the urethral meatus is the opening of the urethra at the tip of the penis. This is where urine ultimately exits.

Causes of Urethral Strictures

There are many causes of urethral strictures. Injury from prior instrumentation or a catheter may lead to scar formation. Alternatively, infection from prior sexually transmitted infections (STIs) may lead to a scar. Inflammatory conditions such as a disease called “Lichen Sclerosis” may cause scar development along the course of the urethra. Any trauma of the penis, scrotum, or undersurface of the scrotum called the perineum may lead to scar formation. For example, a straddle injury from a bicycle or horse may lead to scar formation. In addition, fractures of the bones within the pelvis can lead to instability of the pubic bones and the urethra ends may become distracted from one another.

Symptoms of Urethral Strictures

Urethral strictures can cause a variety of symptoms, from annoying to life-threatening. Before the scar causes complete obstruction, you may complain of frequent urination, having to go to the bathroom urgently, pain with urination, slow urinary stream, or difficulty completely emptying your bladder. Blood in the urine or recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) may also be a sign of a urethral stricture. Over time, the urethral scar tissue may continue to worsen, leading to the inability to pass urine called urinary retention. This may be a life-threatening emergency that can cause damage to your kidneys.

Work-Up and Evaluation

An initial consultation with Dr. Osterberg begins with a history and physical exam. A thorough intake will be completed whereby Dr. Osterberg will review all your pertinent details surrounding your urethral stricture. It is imperative that you bring all your medical records, past operative reports, prior X-rays, or any digital copies of any medical history.

The following procedures may be necessary to diagnose your urethral stricture.

Cystoscopy. A cystoscopy is an office procedure that is the mainstay of the workup and diagnosis of a urethral stricture. First, numbing jelly is put in the urethra to ensure you do not feel any pain. Then a small flexible camera is inserted and advanced to the level of the scar tissue. This study allows Dr. Osterberg to see how far back the scar is, but it does not help to determine the overall length of the scar.

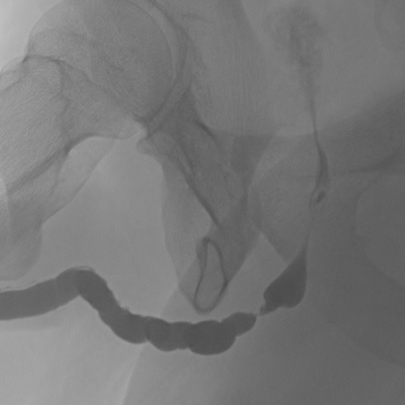

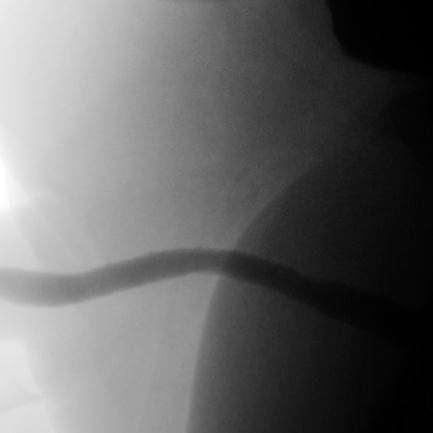

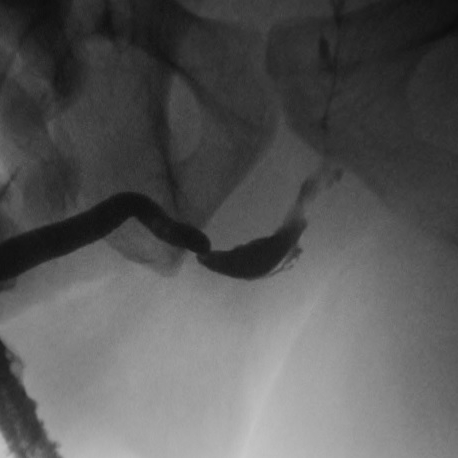

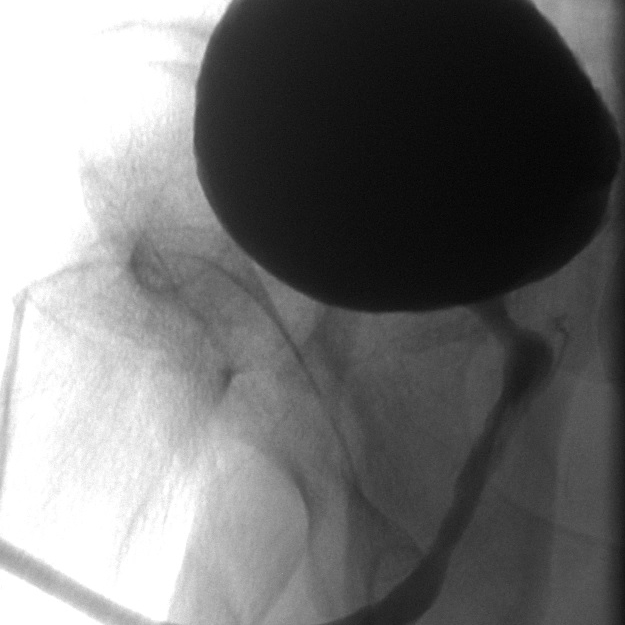

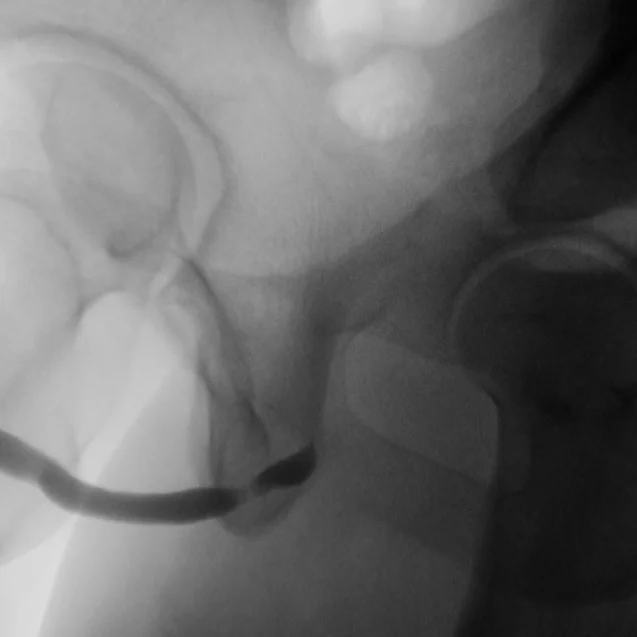

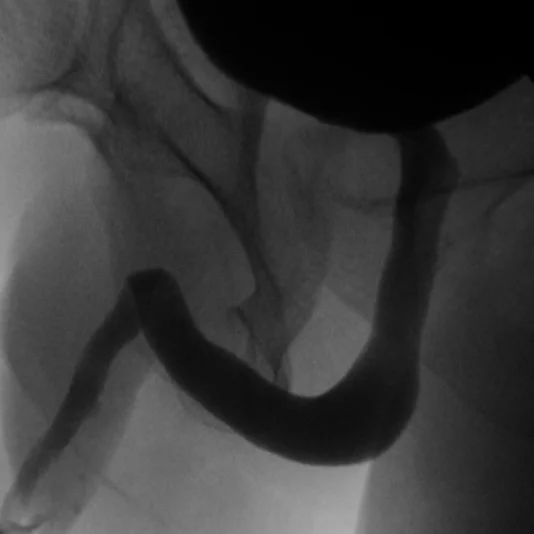

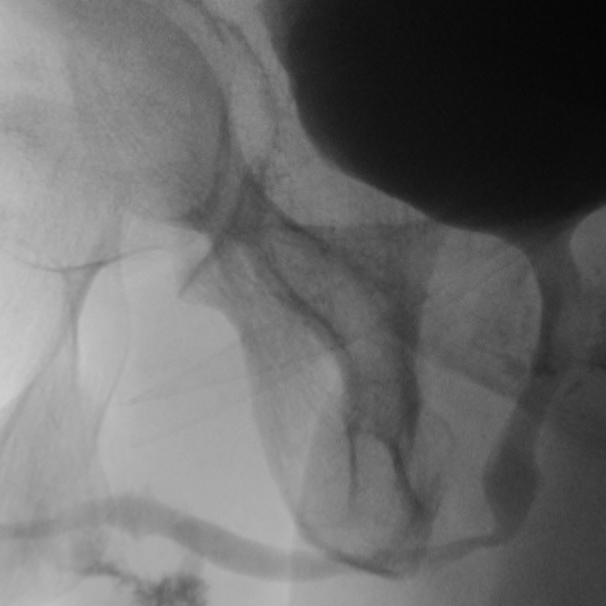

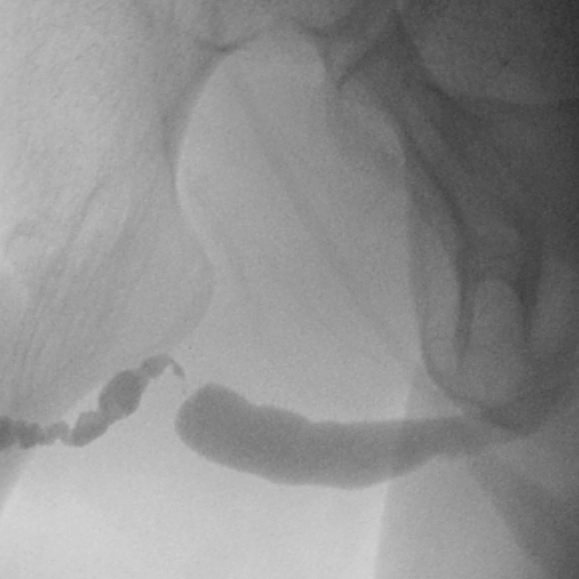

Retrograde Urethrogram / Voiding Cystourethrogram. A retrograde urethrogram (RUG) and Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) are two X-ray studies that provide valuable information to determine the length and location of your urethral stricture. A RUG is performed by injecting a contrast material backward into the urethra. The RUG provides great information on the anterior urethra, however provides very little information on the posterior urethra. A VCUG is performed first by passing a small catheter past your scar and into the bladder. The bladder is then filled with more contrast material. The catheter is then removed and X-rays are taken while you begin to start urinating. The VCUG provides valuable information on the posterior urethra.

Before & After

Treatment of Urethral Strictures

Urethral Dilation. During this procedure, a wire is placed thru the stricture, and over the wire, strong catheters of increasing size are used to open up the stricture. Alternatively, a urethral dilator can be used to stretch open the scar tissue. This option is best for individuals who do not want to undergo surgery. The scar tissue will likely come back (in 50-90% of patients) following dilation so patients must be okay with periodically self-dilating their stricture.

DVIU: Direct Visual Internal Urethrotomy. In this procedure, a special camera lens system is inserted thru the urethra to visualize the stricture, and a small knife within the system is used to cut the stricture in 1-4 areas, opening up the stricture. The procedure is done under anesthesia. The procedure should ONLY be done on short strictures (<1cm) in the bulbar urethra. Long-term success is roughly 50-60%. Following a failure, repeated DVIU procedures should NOT be performed and surgery is recommended.

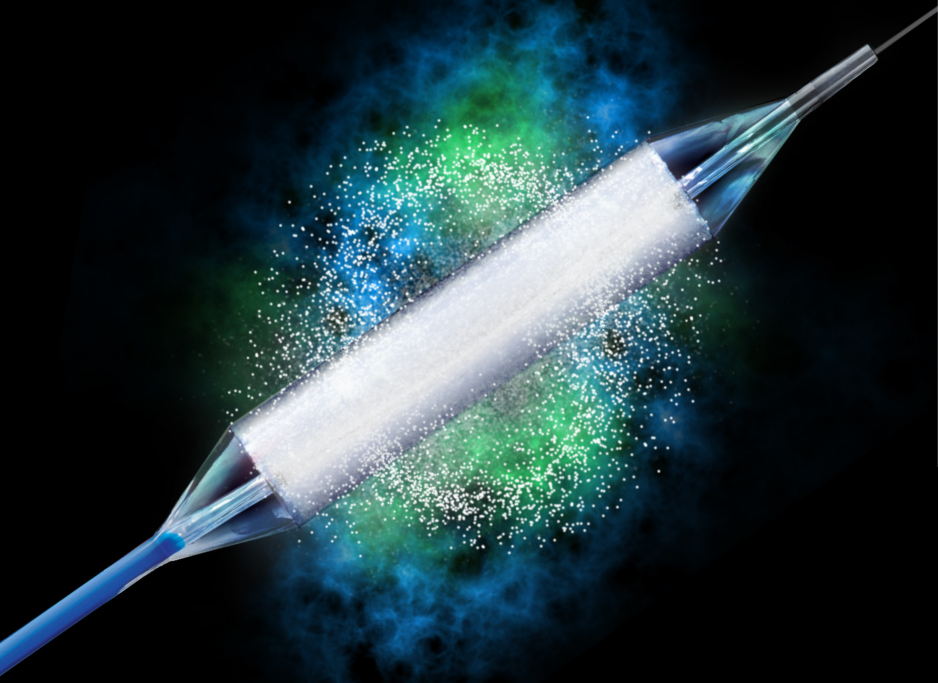

Optilume: A Drug Coated Urethral Balloon Dilation

The Optilume® urethral drug-coated balloon was developed in response to severe patient and physician dissatisfaction with current stricture solutions. The Optilume® technology combines mechanical dilation for immediate symptomatic relief with local drug delivery to maintain urethral patency.

The semi-compliant balloon expands the tissue creating a mechanical balloon dilation effect rupturing the urethral mucosa and allowing direct, circumferential drug delivery to the exposed submucosa through micro-fissures across the length of the stricture.¹

Rapid uptake of the highly lipophilic drug, paclitaxel, limits hyperactive cell proliferation and the fibrotic scar tissue generation that results in stricture recurrence. At 3 years, durability continued with 77% FFRI* ¹, with a 176% increase in Qmax* (Baseline 5.1, 3-year 14.1) and a 65% decrease in IPSS* (Baseline 25.2, 3-year 8.8). Qmax & IPSS are using FCF* rates – Includes worst observed value carried forward for subjects undergoing repeat intervention of the study stricture (i.e. clinical failures).

Urethroplasty (Surgery)

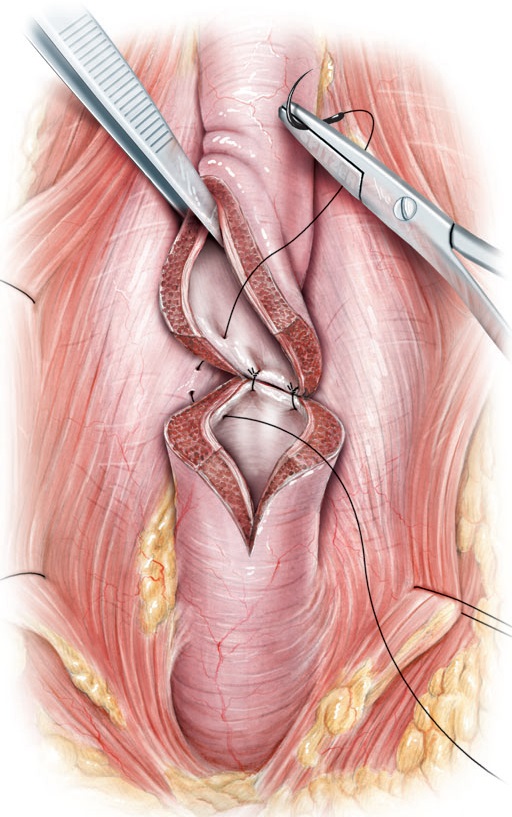

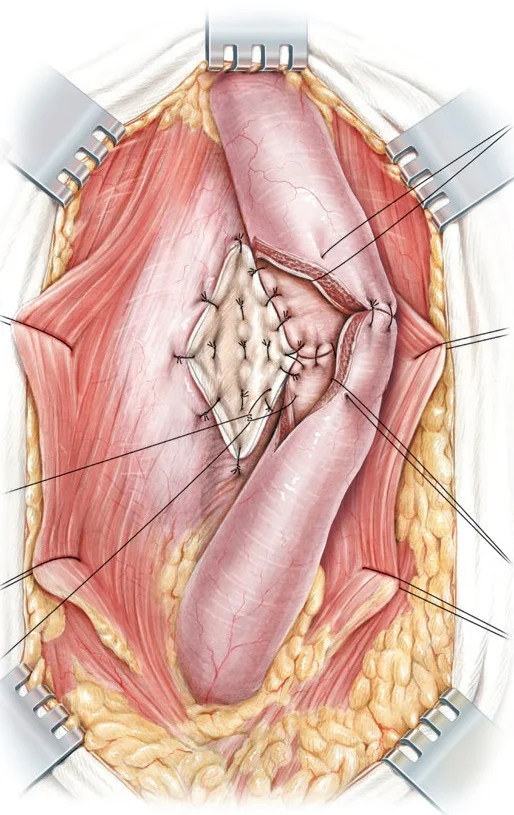

Surgery is the gold-standard for curative treatment of urethral strictures with long-term success rates greater than 85-90%. During the procedure, an incision is made in the perineum (space in between the scrotum and anus) to access the stricture, and several types of repair can be performed:

Anastomotic urethroplasty: stricture is excised or incised and healthy urethral tissue is reconnected.

Onlay urethroplasty: an incision is made thru the stricture and tissue from your mouth (cheek or tongue mucosa) is used to reconstruct the urethra. The graft is called Buccal Mucosal Graft. The most common location is from the left cheek however both cheeks may be needed to gain enough graft to complete your surgery. The inside of the mouth is used because of its rich blood supply, constantly being exposed to a wet environment, and it does not have any hair. The graft site heals very well with no residual effects of chewing, taste, salivation, or dentition.

Fasciocutaneous urethroplasty: skin from the penis or scrotum is used to reconstruct the urethra; this is not favored since it has higher long-term failure rates.

Perineal urethrostomy: the urethra is opened and secured to the skin between the anus and the scrotum; this is favored in patients with very long and complex anterior urethral strictures who are unfit for prolonged reconstructive surgery, who have a buried penis, who do not want multiple repeat urethroplasties, or who do not have enough available graft tissue for reconstruction.

Images Sourced from British Journal of Urology International

Special Conditions That Cause Strictures

Lichen Sclerosis – Lichen Sclerosis (LS) is also known as Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus and Balanitis Xerotica Obliterans (BXO). This is generally an acquired disease of the penis and urethra. It is not cancer (however it is associated with increased risks of penile cancer) and is not contagious or sexually transmitted. The cause is unknown. LS is a scar disease of the penis and urethra and can affect any segment of the urethra. Often, there will be whitish plaque changes to the head of the penis. The opening to the urethra may be smaller or stenotic. The scar may affect just a short portion of the urethra or the entire urethra may be affected. For LS affecting the urethra, dilation is NOT recommended. Formal reconstructive surgery is considered the gold standard of care which may require a graft from inside your mouth.

Selecting The Right Surgical Option

You and Dr. Osterberg will discuss extensively your options. You will review the risks and benefits of each operation. You will review the X-rays and cystoscopy findings together and mutually agree on a surgery with which you are confident. Certain urethral strictures can be repaired or dealt with in a minimally invasive manner, while others may require more formal urethroplasty. Utilizing an expert in male urologic reconstruction for complex repair has been shown to improve outcomes and reduce urethral scar recurrence. Dr. Osterberg has performed hundreds of urethral stricture surgeries so you can be confident you will have all options available to you.

Follow Up

The follow-up after urethroplasty is very important because most urethral strictures recur within the first year or two after surgery. Prior to when you return to the clinic, the bladder is filled with x-ray contrast and the catheter that was placed during surgery is gently removed. While X-rays are being taken, the patient voids and the area of the surgery is evaluated. If the area of surgery is healed, the catheter is left out and patients begin to void normally. This is typically done at 3-4 weeks after surgery. Ideally, within the same day, Dr. Osterberg will also arrange your first postoperative visit.

Thereafter, patients are seen every three to six months in their first year after surgery. At the second postoperative appointment, patients undergo cystoscopy of the urethra in the office and the urinary flow rate and residual urine is measured in our office. The follow-up schedule is individualized depending upon the findings of these exams.